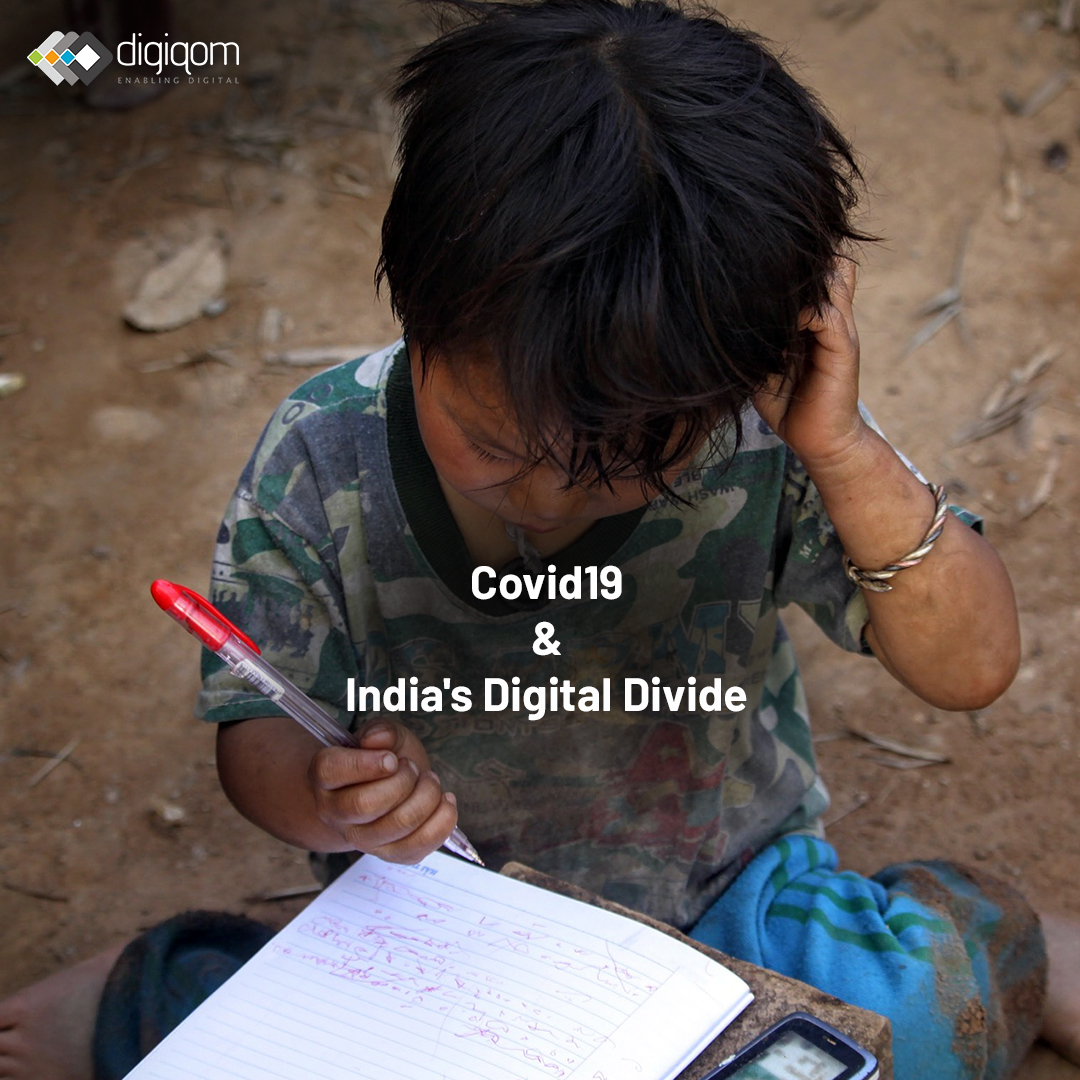

Bridging the digital divide between urban and underserved rural areas has always been a key focus of India’s successive governments and ICT leadership over the years. The recent coronavirus pandemic, however, has revealed the chinks in the armour.

Schools are shut all across the world due to Covid19 and education has moved online. According to the World Education Forum, globally over 1.2 billion children were out of the classroom in April. The nature of education has transformed significantly and e-learning – where teaching is undertaken remotely and on digital platforms – has become a leading mode of instruction.

In India, the switch to online learning has had far-reaching consequences.

When the Central government announced a country-wide lockdown in March, schools and colleges instantly moved to online learning. While institutions in urban areas were able to make the switch smoothly, their rural counterparts were not so lucky. A villager in Himachal Pradesh was forced to sell his cow as he didn’t have the money to afford a mobile phone for his children’s online lessons. His plight moved many to tears on social media and there was an outpouring of help to fund his children’s education.

Aishwarya Reddy, a mathematics student of Lady Shri Ram College for Women in Delhi was not so fortunate. She died by suicide recently as she couldn’t afford a laptop for her studies. The instalment of her scholarship that was due in March had been delayed and the student did not want to trouble her family for money. A resident of the Rangareddy district in Telangana, she was the state class 12 examination topper and had mortgaged her house to fund her higher education.

Out of the 1.26 billion children worldwide out of school due to the pandemic, over 320 million are in India. With a population of over 1 billion, the government has a challenging task in ensuring universal elementary education. While there has been an increase in the number of educational institutes in the country, especially over the last few years, the problem of literacy in rural areas and among the female population still remains unsolved.

According to the Key Indicators of Household Social Consumption on Education in India report, based on the 2017-18 National Sample Survey, less than 15% of rural Indian households have Internet (as opposed to 42% urban Indian households). A mere 13% of people surveyed (aged above five) in rural areas — just 8.5% of females — could use the Internet. The poorest households cannot afford a smartphone or a computer.

With the pandemic, this gap between the urban and rural areas has become even more prominent. A few of the reasons contributing to lack of access are:

Unstable Internet and electricity connectivity: Ironically, though we are among the largest consumers of smartphones, a strong broadband connection, stable electricity and Wi-Fi networks in many underserved areas is still a distant dream.

Language barrier: Most of the digital content available is in English and Hindi. Inadequate representation of vernacular languages make it difficult for many across the country to access online learning.

Teaching training and technology infrastructure: The governments in different states need to collaborate with private companies in the EdTech domain to ramp up technology infrastructure and invest in teacher training.

Over the past decade, governments have undertaken many initiatives to improve internet access and literacy in the country. In 2014, the government launched National Digital Literacy Mission and the Digital Saksharta Abhiyan. In 2015, the government launched several schemes under its Digital India campaign to connect the entire country. None of these seem to have been enough.

Given the glaring gaps being brought to prominence by the pandemic, clearly a lot more needs to be done. Or else the government’s universal education access will continue to leave behind the girl child, as well as the more socially and financially disadvantaged rural children. Not to mention the collateral damages in terms of the lives lost.

Debeshi Gooptu